- Home

- William Thacker

Lingua Franca Page 3

Lingua Franca Read online

Page 3

‘It’s a well-oiled machine,’ the councillor says, doing his best to get Eden’s attention, which must be irritating for Eden. It’s hard enough for Eden to concentrate on his lines without having some ignorant fool leaning over. Eden is able to look up and half smile while remaining focused on the call. It’s quite a feat to be able to manage both things at once. He manages to put the same effort into pleasantries as he does the phone calls. He once told me that it’s a relief to come here. At home, all he does is argue. ‘He’s good,’ the councillor says, which Eden would have heard. By the time Eden has finished with the call, and risen from his seat, it seems that half the room is watching him.

‘Who was that, Eden?’

‘Basingstoke.’

‘What are they saying?’

‘They want to change their name to something vibrant. An energy drink, or something.’ The sales board features a grid of names and roman numerals. Eden rubs the ink with a sponge. He writes another digit in his column, another stay of execution.

‘Have you got the direct debit?’

‘It’s done.’

There is a holler. Some of the lads congratulate Eden; some of them ignore everything. Nigel offers a hand. Everyone takes it in turns. Here we are – a functioning business. The councillor doesn’t offer a hand but he smiles from a distance. It will make the councillor feel less vulnerable to know that some other town is joining the party. It’s happening. Eden is unmoved by it all. He’s reluctant to accept the handshakes. He doesn’t seem to care, aside from the simple numbing pleasure in making a sale. It’s a balm. He has the ability to live for another month. Eden picks up the phone and dials another number. The sales team is required to stay until six o’clock, which is later than everyone else – except the cleaners, who are just getting started. Then it all subsides and everyone returns to their desk and realigns their work-face.

Someone calls Grimsby to find out whether it wants to change its name to Qatar Airways.

The after hours involve strategic planning, which essentially means listening to Nigel talk about how things ought to be different. This is the time of day when ideas emerge. It’s clear-the-air time, when the day’s successes and failures can be viewed for what they are. It’s also when we gossip in the only way certain types of men can do: we discuss who’s fat and who ought to throw themselves off the roof. Through the glass we can see Eden sitting at his desk, a Gormley statue. He likes to stay behind afterwards. It’s the only time of day that he’s able to check his emails. Eden invites suspicion by his own intelligence. Something must have gone wrong.

‘I think he’s been drinking,’ Nigel says.

‘How do you know?’

‘I could smell it on his breath. He’s probably drunk right now.’

Within these walls, no one can hear us. I’ve tested it from the other side. This is our glass incubator. Eden looks at us and raises a hand to say goodbye. He does everything in a swift, uncomplicated manner. The way in which he grabs his coat from the rail is for the purpose of getting out fast. I tell Nigel that I’m going for a walk. It’s satisfying to be able to step into the office and observe a quiet room, absent of telephone chatter. The entire floor is quiet at this time of evening. Most of the other business owners have already gone home. Eden walks towards the secret lift, which is reserved for parcels. It’s the one time of the day Eden doesn’t care about doing the right thing. I wait until the beep of the lift sounds. I take the lift to the ground floor and exit via the main doors, making sure to waft my security pass in front of the guard, who asks to see it every day. The route to the station follows a bend, from which it’s possible to see Eden walking ahead and talking on his phone. He’s probably telling his partner about how much he hates the job, and how everything will be alright once he gets a better one. Eden’s walking fast enough so that no one could catch him without running. He crosses the road without much regard for the oncoming traffic, which means he gets a head start on me. He wants to get home as fast as he can. He doesn’t want to dawdle or look at the view, which consists of a motorway underpass and hedgerows with cigarette butts. There’s a grey apartment block that’s considered retro and cool in the eyes of people who don’t have to live there. Stella Artois, which was once called Milton Keynes, doesn’t have a centre. There’s a central commerce district, but it feels more like the central square in a grid than the pinnacle of anything. It’s just the same as all the other squares, except for the flat-box train station and the large Mecca Bingo. Its ugliness has its own determined beauty. It makes no concessions to anyone. The purpose of the exercise is to watch Eden from afar, and see how close I can get. He’s fortunate that I’m very unfit. If it were possible, I’d follow him all the way home and observe him from the garden window. I’d watch him sitting at the kitchen table while his partner – a sexual health nurse – starts an argument about money. The lack of money is nothing compared with his lack of purpose. I turn the corner and witness a surge of office workers emerging from the station. Hundreds of people criss-cross and manage to avoid contact like well-behaved atoms. Eden doesn’t want to push, but he’s forced to. It’s the only way of getting past. It’s possible, with some persistence, to find a way through. There are enough polite people to make it possible. The queue makes it look as if there’s something exciting to wait for, but it’s just a train ticket barrier. I wrestle through the crowd. Through all this, it’s possible to see Eden, who swipes his season ticket against the scanner, proceeds through the barrier and consults his phone, no doubt for job ads or angry text messages. The speed at which Eden walks almost suggests he knows I’m coming. This is the point at which we lose contact, and I can no longer see what I want to see. That’s the end of it. I won’t be able to reach him. He’ll be in a rush to catch the 18.56 to Vodafone.

04. BEHAVIOURAL FRAMEWORK

We refer to it as the bribe. The regular knees-up where we make them feel valued, so long as they don’t ask for better working conditions; and so long as they upload pictures on social media so that everyone thinks we’re a fun company. It’s an integral part of our brand-building strategy. After all, you can’t share an image of an insecure job, but you can show the world that you work for Lingua Franca, who put money behind the bar and will lend you all the confetti you need. On Halloween we give them apples to bob. On Valentine’s we give them scissors and glue to make heart-shaped cards. At Christmas we take them for dinner and attendance is compulsory. We present it as a reward, which isn’t wrong exactly. They like getting drunk.

The pub is located at the bottom of our building. The customers include office workers and tired, drunk men who sit at the bar all day. The lighting is bad and not in a soft, candlelit way. No one has taken the initiative to draw the curtains. I have nothing to do with ordering drinks – that task belongs to Nigel. I lean on his shoulder and whisper the pin number: 1985. My involvement extends to buying alcohol for everyone. It means I can opt-out when it comes to any social interaction. My strategy is to hover, which gives me the choice on whether I want to escape. There is a corner section, which Nigel reserves every time. There are people trying to get my attention from either direction. Some of them tug at my sleeve and some of them tap my shoulder. Everyone says things like ‘Sit with us, Miles!’ A couple of them shuffle along to make room at the table. I sit next to Eden.

It’s Eden who starts the conversation. ‘You alright, mate?’ I tell him I’m alright. ‘Good week for sales,’ he says. He mentions the problem of updating the sales report, which has been locked for editing. I wonder if Eden really wants to have this discussion. He’s twenty-odd, but he looks much older. He’s got close-cropped hair and blue-toned bags under his eyes. He looks in need of a spa detox. Someone should straighten his back and de-clog his pores. Much of his chat relates to work and how he should have closed a deal for Wigan or Scunthorpe.

I tell him, ‘It’s alright, mate. You’ve worked hard. You’re a high-quality individual. And that’s what we need at Lingua Franca.�

� He gives a solemn nod. ‘As far as you’re concerned, the sky’s the limit. Office manager… head of sales…’ He appears to lose concentration. It’s as though I’ve flicked a switch and turned him off.

‘Excuse me,’ he says. Eden gets up and walks through the double doors.

The rest of the group cheer as Nigel puts a tray of pint glasses on the table. They’re glad to receive the drinks; they’re lost desert explorers in receipt of water. There are two distinct tribes: the graduates and the sales team. The former exist in a permanent state of disappointment. Their academic selves had imagined a different future, a world where ideas were important and young people could make a difference. They assumed they would exist like characters in their favourite books and films. They arrived in an office job and wondered whatever happened. The sales team has different expectations. They drink beer rather than wine and they’d rather visit Benidorm than Brixton. They’ve already glimpsed an alternative world. They’ve worked in shops, gyms, supermarkets, pubs, catering halls, kitchens and call centres. In light of this, they’re delighted to work for Lingua Franca. They’re amazed they’re able to wear a suit, or look at their name on an entry pass. Unlike the graduates, the sales team never had a dream to begin with. What unites each tribe is that they like being drunk. They like being drunk more than they like drinking. As a group, almost all the chat concerns work. They talk about how they’d do things differently, if only they were in charge. It moves onto a discussion about who should date whom, and who’d make the prettiest couple. Even if some of them laugh, they’re secretly keen to hear the verdict. It descends into a bout of in-jokes, a competition to see who can tell the best stories. No one is very good at listening. Nigel serves no purpose in this context other than to keep a lid on any chaos. He will permit the group to go wild, provided there are predefined terms which stipulate what exactly is meant by wild. Good, clean fun and all that. My plan – to dissolve into silence – is executed well. The only threat comes from the drunk barstool men who try to make conversation with the women in our team. When no response is offered, the men start swearing for no apparent reason. One of them makes an obscene gesture. Nigel is watching without saying anything. And in any case, he would make the feeblest of security guards. He looks in my direction to see if I’m safe. One of the posh hedgehog graduates tries to raise an objection with the drunks; they squabble for a moment and come to an understanding that the hedgehog should just accept the abuse. Finally, the men find someone else to harass.

I tell Nigel I’m going. He’s reluctant to let me walk alone, but lacks the authority to tell me what to do. Nigel clinks a glass and the rest of the team fall silent. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, may I have your attention please?’ Nigel thinks he should talk like this because he’s second-in-command and second-in-command beats all the rest. ‘Let me draw your attention to Miles, who would like to say a few words. Come on, Miles. Give us a speech.’

They all bang the tables and chant ‘Speech, speech, speech!’ The vibe is friendly rather than a desire to see me fail. ‘Umm… thanks, everyone.’ My job is to focus their minds on what’s important: drink, money, survival. I have little to say, which means I raise a glass and propose a toast. I address them as individuals as best I can. I praise the sales team for their efforts in promoting Lingua Franca. I congratulate the web designers, coders, marketers and admin bods. We have a brilliant team, I remind them. We will travel to Barrow-in-Furness and create a spectacle for which Lingua Franca is renowned. ‘Let’s remember why we’re here – yes, to recast the English language and make our mark on history. But friends, we’re also helping to change the direction of travel in towns up and down the country. Ask Doncaster. Ask Waterstones. At a time when local budgets are being slashed, we’re the ones giving towns a new lease of life: a foundation, a future. We’re proud that we make a profit, but proud, too, of our ability to make a massive impact.’ They applaud. They look at me as the favoured one, the cool art teacher to Nigel’s deputy head. ‘Don’t forget, you’re history makers. When someone compiles a history of the English language, there’ll be a chapter marked Lingua Franca.’ I’m speaking to an audience of drunks. They’re at their most supportive but least capable of comprehending the words. ‘So, let us raise our glasses… to us!’

*

The beauty of the compound is that you can imprison yourself easily. If anyone were to force entry, they could only proceed were they to make lots of noise. Ptolemy’s eyes widen, which means that someone’s approaching from the gravel path. She’s ready to pounce on my behalf. The good thing about Darren is that he’s always on time. I could ring for Darren at four in the morning and he’d come along. The security industry has an unintended egalitarian trait – taking kids from the streets and giving them a job. They employ kids like Darren and tell them it’s a good thing to be a tough bastard. Darren’s firm offers to protect high-risk clients: Quran defacers and tabloid witch hunt victims. I’m one of their most reliable customers. There was a period following the renaming of Stoke-on-Trent that Darren became a permanent guard-in-residence at the compound. The alert level has since been downgraded, but only a little. There is no dignity in having to leave the house with a security guard. It would be nice to walk alone, if the risks weren’t so great. Even now, eighteen months since Milton Keynes became Stella Artois, many of the townspeople would like to make my life as difficult as possible. The charge is that I’ve degraded language and undermined what it means to belong to a community. They ask me rhetorical questions like where does it end? I tell them there doesn’t need to be an end. This is only the beginning.

Darren doesn’t look well. His eyes tell me this. It’s not something he’d admit to, even if it were obvious. He needs to pretend he’s strong enough to cope with anything. ‘Good morning, sir.’ He doesn’t really mean it when he smiles. He probably gets advice from his mum. She’ll say, ‘Whatever you do, just tell him he’s brilliant.’ He’s been told what to do for so long that he can barely remember how to think. He soaks things up. ‘Shall we go straight to the office this morning?’ I nod. There’s no danger as we walk, and it’s not certain what Darren could do even if there was. He’s a deterrent. He could be capable of anything, or nothing at all.

The neighbourhood is a mixture of clean and dirty money: doctors and drug dealers, rich pimps and hedge fund managers. There’s always construction work happening, a constant drilling and the sound of wood being thrown into a skip. Every so often you see a white van patrolling the street – the remit is to identify non-residents and tell them to leave. Behind the railings, the trees are so high you can barely see the houses. The street names reflect a pastoral past, which in a modern context, feels like some sort of joke. Lambton Avenue means ‘the town where lambs are sold’. Nothing like this happens anymore.

Darren looks through a gate. ‘Some big arse houses, man.’ Darren lives with his mum in a modest block of council housing surrounded by metal bins on wheels. We exit through a gate and enter the real world, where roads are public, not private, and people don’t stop you from looking at their house. I mention the previous night, and how everyone got drunk. Darren does a good job of disguising his disappointment he wasn’t invited. The further we walk the more it seems like we have nothing to say. For Darren, it’s an exercise in walking the dog. I should bark when I want to go home.

‘I don’t know, Darren. Sometimes I think I should be doing more with my life. Do you ever get that?’

‘No, sir.’

‘If there was an asteroid that destroyed everything on earth, what would I have achieved?’ Darren’s too afraid to speak. ‘Can I tell you a secret, Darren?’ I don’t want to hear his response. I’m telling him a secret. ‘I’m a slow reader. I used to teach English, but I read none of the books. I taught a whole course using SparkNotes. I’m good at collecting books, but not so much reading them. You should see my shelf. Kendal says—’

‘Raaa!’ Darren says, pointing at a hubcap on the kerb. He looks at the hubcap, which

has no novelty, other than the fact it’s fallen from a wheel. The normal order of planetary events has been disturbed. Then Darren seems to realise he’s gone off-script – the script being to listen to whatever comes out of my mouth.

‘But you know… maybe it doesn’t matter that I don’t read. It’s good to be a charlatan. Being a charlatan takes talent.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘I like to read about books, though. I could tell you lots of different opinions on the Bible, but I never want to read the Bible itself.’

‘The Bible’s boring, man.’

‘Exactly.’ I put a stress on exactly only because I want Darren to say something. ‘Sure, it would nice to read more. But it’s not like anyone at work’s gonna test me on Anna Karenina. I’m a qualified… language creator.’

The conversation runs aground. We’ve talked for as long as needed. We walk past the old house where Kendal and I were supposed to live, and where she still does. It’s an Edwardian house, somehow still intact despite the wrecking ball damage all around us. She hasn’t bothered to mow the front lawn in months; the grass is wild and uneven, with a wheelbarrow almost hidden from view. She needs to do something about the broken guttering. At the gate is the problem tree. It needs a tree surgeon to trim the roots, or the house will fall over. She’s done nothing about the tree.

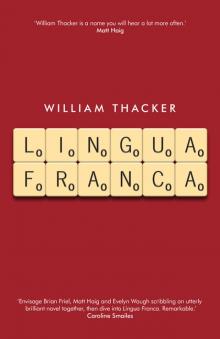

Lingua Franca

Lingua Franca