- Home

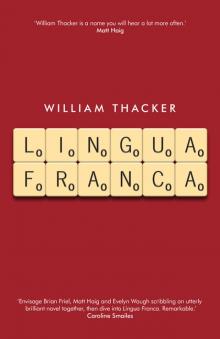

- William Thacker

Lingua Franca Page 2

Lingua Franca Read online

Page 2

Around the circle there’s a positive murmur. ‘I think it sounds classy,’ someone says.

‘Thank you, localisation.’ Nigel points at the tech team, and we listen to nothing anyone understands. We go round the circle, which includes the accounts department, publicity and general admin. When it gets to my turn, my only contribution is to remind everyone to empty the fridge so it doesn’t start to smell. Everyone seems to find this funny. I’m the warm, fuzzy segment at the end of the six o’clock news.

‘Thank you, Miles. That’s a wrap, folks!’

It starts again, the noise: the sound of telesales men getting impatient, the photocopier scanning something, the huge server trying to out-hum the air conditioner, the absence of music, the measured tone in everyone’s voice. The lads get back on it, reconfiguring their work face and lifting the receiver. They all know the rules – they’re hungry salesmen and they need to eat. I often forget their names.

*

‘I don’t hate you, Miles. You’re just in charge of the most appalling cultural phenomenon in decades. You’ve made it your personal duty to kill the English language and replace it with corporate fluff. You’ve taken something beautiful and made it ugly.’

‘Do you still want to have lunch?’

‘Only if you’re going to apologise.’

‘For what?’

‘Ruining the world.’

Kendal has been holding a pen while making the point. I thought the pen was going to snap. She doesn’t understand what it takes to maintain the competitiveness of a multi-million pound business. She doesn’t care about these things, and wouldn’t care even if I gave her a ten-hour lecture on its importance. We both like to argue for the necessity of our existence while being secretly jealous of the other. ‘Woe, destruction, ruin and decay,’ she says. ‘The worst is death, and death will have his day.’

‘I’m not listening.’

‘Are you ready to die?’ Kendal says, but not like a murderer might say it. She enters the kitchen and lights a cigarette on the hob. She peers through the bulletproof kitchen window and says, ‘I don’t want you getting killed. As much as you fucked up our lives, I do care about you… a bit.’

‘I’ll be fine.’

‘Jesus, you can’t even open a fucking window in this place.’

‘Pull it towards you.’

She gets it open. She leans her head and blows out smoke. She looks at the courtyard, no doubt reflecting on her hatred of the compound. It’s the most expensive development in Stella Artois, and certainly the most security conscious. The apartments have perimeter walls with sharp, metal spikes. The courtyard gravel amplifies the sound of footsteps. Hidden in the lamp posts are surveillance cameras. A nightwatchman sits watching snooker in a security box. The concessions to beauty come in pastiche-form: wisteria on the walls, spurious Latin inscriptions. The development wants to belong to every period of history except this one. ‘For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,’ Kendal says.

Ptolemy follows me into the kitchen. Ptolemy has thick grey fur. You can run your hands through it. I wouldn’t do well with a short-haired cat. I wouldn’t like to feel its spine. Ptolemy looks at me and I can sense what she’s thinking. You bastard. She hasn’t been fed all day. ‘No one fed you, did they?’ I find myself saying. I scrape jellied meat into the bowl. She sniffs at the food. If she were a human she’d be a demanding child, unaware of her privilege and suspicious of giving anything a try. ‘Come on, baby.’ She licks the food and all is forgiven. ‘Good girl.’

Kendal stubs her cigarette on the window ledge. ‘Is this part of your decline? The cat thing.’

‘I’ve been doing this for years. You just weren’t paying attention.’

‘It’s part of your decline.’

The noise of the boiling kettle scares Ptolemy and she dashes to the living room. Kendal begins to moan about teaching and the educational standards in Stella Artois. She’s tired of explaining the difference between you’re and your. Over the years, Kendal has undergone various incarnations: the student idealist, the almost-mum to our almost-children, and finally, the deflated mid-life Kendal – the one who teaches English. We used to joke about how Kendal filled our moral hardship quota, which gave me license to do evil. She took one for the team. I don’t have any backup now. No one’s doing good on my behalf. I’m evil-plus.

‘Do you think we should move in together?’ she says.

‘No.’

‘It can be completely soulless, Miles. I can just live off your money and we can have sex with whoever we want.’

‘I think that’s what happened the first time.’

It ended like most of these things do. It got to the point where neither of us wanted the same things. I didn’t want to have children; Kendal didn’t want to support a naming rights consultant responsible for the death of the English language. In her heart, Kendal doesn’t want to come home. The pragmatic mind, which weighs the importance of mortgage repayments, might decide I’m worth a second chance. The heart says no.

On the table is the Lingua Franca brand catalogue, the 48-page booklet that details our creative vision. The first page says: In the beginning there was the word. Kendal smiles as she turns the pages. She shakes her head at the image of a waterfall juxtaposed with the word MoneySuperMarket. ‘Miles, Miles, Miles. You were beautiful once.’ She feels my old tweed jacket wrapped around the chair. She looks at the bookshelf for evidence of my decline. ‘Oh dear.’ She picks up a copy of Naked Lunch and shakes her head. ‘This isn’t you. You’re not a Burroughs fan.’

‘You don’t know what I read.’

‘You’re a slow reader, that’s what you are. Where are all the marketing books about ripping people off?’

‘With the books about bitter ex-wives.’

‘Current wives.’ She fondles the key in the bureau lock. ‘Unless you’ve got some divorce papers in here.’ She spots something else. ‘Oh, what?’

‘Stop looking at my books!’

‘When was the last time you read Audre Lorde?’

‘There’s no time.’

‘I know you, Miles Platting. You’re not a feminist. Are you trying to impress a lady?’ I feel naked. ‘You shouldn’t be allowed to own that book. You can’t do all the shit you do, then try and own Audre Lorde. Sure, you can put Lorde on your bookshelf but that doesn’t mean you own it. Miles Platting, destroyer of worlds. Likes Audre Lorde.’

‘Why don’t you take some books home? I know you’re hard-up at the moment. Put it in a doggy bag.’

She sticks up a middle finger. In these encounters, we like to road-test our best material. She doesn’t mind talking about her poverty, but not to be reminded of it. She puts Audre Lorde back, a different spot to where she found it. She knows that she’s ruined my alphabet. ‘Oh, Miles, Miles, Miles.’

‘Kendal, Kendal.’

‘I’d better go.’

She looks in the mirror and pretends to be uninterested in her reflection. She used to have long hair but now she has a short pixie cut where most of the effort goes into coiffuring the front. It’s a haircut that says fuck you, Miles. The act of leaving requires my assistance. The access code is 1985. It was originally 1984, but Kendal advised that 1984 is the first code that burglars try, so long as they’re literate. She looks at me. The only word I can think of is pity.

‘Don’t get killed.’

‘I won’t.’

Ptolemy watches from the piano. She likes to watch people from a great height.

‘My class has exams tomorrow. I think they might fail on purpose.’

‘It’ll be fine.’

‘Wish me luck.’

‘You wish me luck as well.’

‘For what?’

‘Staying alive.’

‘It’s not a contest.’

It goes on like this, and it turns out that neither of us wishes good luck upon the other.

‘I don’t want to say goodbye like this.’

‘How sho

uld we say it?’

‘Say something nice.’

I explain that if I could do anything, I’d buy Paris and change its name to Kendal. She allows herself to blush.

03. THE ENGLISH CHICAGO

It begins with a sweeping shot of the ocean. On the horizon are the rusting cranes of Barrow-in-Furness. Everything looks cold. It’s hard to decide whether the sea looks green or grey. The clouds have no problem with raining on the town. There’s not much in the way of action, besides a slow-motion ship coming into the slipway. The next thing in sight is a fishing boat, from which it’s possible to make out the town as a silhouette. All you’re meant to know is that Barrow is a place, and it’s distant – unattached. None of us need to worry. This is as close as any of us will get.

‘This is Barrow,’ the narrator says. ‘It used to be one of the proudest towns in Britain.’ We accelerate, moving into the town. We reach land, and the rows of houses become dense and repetitive. We can see the town for what it is – a grid of terraced houses and a church in the middle. ‘Life in Barrow isn’t what it used to be,’ the narrator says. We see a checkout girl in a supermarket; she’s scanning items and shaking her head. It’s not the Barrow she once knew. An elderly man is waiting to cross the road but none of the cars are willing to stop. What will bring Barrow back to life? If the video is to be believed, what’s missing is the magic. Not money, of course. It’s just the magic that’s missing. The images come faster now. A recycling skip is piled with wet cardboard. The playground is empty – a swing rocks back and forth. Next is a young boy. He’s bouncing a bright orange ball in slow motion. This is the only way any of us will get to experience Barrow. We’re watching from afar. We might be able to visit when the magic happens, and people start smiling, but not until then. ‘Barrow deserves better,’ the narrator says. ‘Barrow deserves Birdseye.’ Suddenly there is colour. The seagulls are racing home. A little boy is walking hand-in-hand with his sister. It’s a montage of images in which women laugh, children run around and nothing bad appears to have ever happened. A crumbling school building is being painted white. The checkout girl is smiling. The town seems content with itself. What was ugly can become beautiful in an instant. Peace is all around us. The slogan says:

Birdseye-in-Furness: The Promise of a Brighter Barrow.

There’s a problem with Barrow, but it can be fixed. You just need to change the name to Birdseye. Everyone applauds once the credits roll. The reaction is the same as ever – the same as Skegness, Skelmersdale, and all the others that came before. Just like Runcorn and just like Redcar – everyone applauds, as if the video can hear us. I make eye contact with the front row – the town council representatives of Barrow-in-Furness. What stops them from smiling is their basic instinct, which tells them that Barrow-in-Furness should always be called Barrow-in-Furness. It shouldn’t be known by any other name.

‘As you can see, we’ve matched Barrow with a brand that recognises its maritime history. The naming rights will cover all maps, road signs, transport timetables, public buildings, digital media and more. Members of the media will be duty bound to substitute the name Barrow-in-Furness for its replacement, Birdseye-in-Furness. Yes, there will be a certain amount of residual anger. The typical cooling off period for the public is six to eight weeks. A critical mass should begin referring to the new town by its brand name after about three years. A unanimous transferral of loyalty from one name to another can take generations. With the right brand, though, it can happen a lot sooner. And we believe we’ve selected the right brand at the right time.’

In my attempts to describe what we’ve just watched, I sound almost professional – a scholar. They must imagine that I’m qualified in something other than talking-a-good-game, or selling town names for a competitive rate. I’m not a linguistics professor, sadly. I have no grounding in the study of language other than my ability to sell it. I’m not a professor of anything. I’m a man with an idea. I got some money from an angel investor. Nigel liked the concept and took a nominal salary. We got a sales team of cheap school-leavers and outsourced technical work to a company in Bangalore. Our first clients came along – bankrupt town councils like Congleton and Kettering. Then came Didcot and Dudley, Barnstable and Penrith. All of them wanted to make a statement that change is coming and renewal is on the way. You just have to change your name to Birdseye. ‘It’s not just the town name that can be sold. We offer a premium package for the right to sponsor street names, public squares and neighbourhoods. Here at Lingua Franca, our service is tailored to the exact needs of every client.’ I’ve been practicing this for months. Sometimes I spend twenty minutes in front of the mirror, talking aloud about the benefits of naming rights. It’s easy to make the argument at this point; the town officials start to think about their property values, and how they might retire in peace and comfort. Lingua Franca will make your town rich. Businesses will invest, wages will rise. The town will feature in property supplements. No one could possibly conclude that selling Barrow’s naming rights won’t result in prosperity for all. They’re getting it now. They’re beginning to see what Lingua Franca can do. They weren’t fully sold at first – more like half-in, half-out – but now they’re getting it. We can all get paid. We can exchange the habits of a lifetime for something more tangible – money. Barrow-in-Furness whisper among themselves, conferring like game show contestants. Without Lingua Franca, they wouldn’t know how to promote Barrow, and how to position themselves in the marketing world. They probably don’t understand what’s going on.

‘Thank you very much,’ the councillor says. ‘I think we’re ready to proceed.’

Change is coming. By the morning, we’ll have another red pin on our British Isles map.

The next stage is to take them into the office, a process designed to convince them we know what we’re doing – which, in fairness, we do. They’re welcome to step into the office and review the procedure by which their town will be branded and sold to the world. The office itself has been designed with the intention of relaxing everyone. There is a floor-to-ceiling image of a woodland path. It gives the impression – completely contrary to our business activities – that we have anything to do with planet earth. You can hear everyone typing when it’s quiet like this. Normally, the office has a natural rhythm, which doesn’t allow for silence. There is a massive clock on the wall, which everyone pretends not to notice. I permit the town officials to walk around the office, doing as they please, which involves looking at the sales team and waiting for some kind of clue, some kind of guilt. The clients don’t actually pay for this service – I’ve checked the terms of usage – but it makes sense to allow the illusion.

‘Barrow will be at the vanguard of modern town branding,’ I say aloud. ‘Look what we did for Watford.’

It’s only when I raise my voice, and reaffirm the premise of Lingua Franca, that our friends from Barrow begin to animate. ‘Is there a security risk?’

‘Not in the slightest.’

The councillor doesn’t really know what he’s looking for. He walks around, peering under the tables. He probably thinks he’s going to find something suspicious. The councillor’s distinguishing feature is his creased forehead, which overhangs – protrudes is better – so that his nose and lips seem squashed-in. You get the sense he might ram you with his forehead before he shakes your hand.

‘Looks good, that,’ the councillor says, pointing at the screen. From his accent you can tell the man is from somewhere in the north. Somewhere rich, though. The incongruous north. We stand around a computer, looking at an image of Barrow-in-Furness. The designer has done an excellent job. It looks nothing like Barrow-in-Furness.

Nigel emerges to say, ‘It has an alpine quality – a kind of Sydney Harbour, but with an alpine quality.’ Nigel explains the next stage of the process, which is the launch. We’ll arrive in Barrow, christen it Birdseye, and keep a safe distance from the town. There will be a naming ceremony with dignitaries in attendance. It’s a circus,

yes, but a highly profitable one. The circus needs a ringleader, and our duty will be to stand in front of a crowd and herald the Birdseye revolution as the best thing ever to happen to Barrow.

I introduce the officials to the project delivery team, whose emphasis is on design, content and PR. These people are graduates, desperate for work and always keen to show me what a good job they’re doing. There’s an intern, who is keen to smile at every opportunity. It’s not that she’s friendly; she just knows who I am. This is disconcerting. It makes me think she would do anything for money. The geeks and creatives work in tandem to create slogans and pictures. The purpose of their labour is to convince the world that Birdseye is worth visiting and worth our attention. It’s not Barrow, for one thing. All of them are plugged into our mindset – that town sponsorship means money, and money means happiness.

The councillor continues to twirl the key fob chain. It’s a temporary pass, and he shouldn’t be twirling it. He looks at the bank of telesales staff like it’s something he’s never seen before. ‘Ah, the engine room,’ he says. The sales team want to be left alone. No one wants to engage in faux-banter when you’ve got calls to make. They degrade themselves in exchange for money. They deserve the decency of being left alone. Suddenly, everyone’s selling at the same time. It’s hard to decipher the words. It’s reminiscent of commentators getting excited as the horses reach the final furlong.

‘Good afternoon, you’re speaking to Eden at Lingua Franca. We are the UK’s number one naming rights agency. Who can I speak to about naming rights for the town?’ Eden has the ability to bullshit on demand. He’s a seasoned performer when it comes to bullshit. The tone is sharp – it’s the sound of someone who’s spent ages perfecting his voice. It’s a kind of professional register that doesn’t exist in normal life – no one would speak like this unless instructed to do so. ‘Here at Lingua Franca we provide hassle-free naming rights solutions. What we offer is a comprehensive end-to-end solution – we will partner with your town and give it the exposure it deserves.’ I find myself nodding, without realising, until it becomes apparent that Nigel is looking at me. ‘Would it be a good idea if I popped you some details in an email, sir? I can promise you – it’s a real thriller.’ Eden can do a good job of sounding enthusiastic. The thing about Eden is that you never quite know if he’s going to have a breakdown. He doesn’t live for the simple pleasure of getting a pay slip, which guarantees drinking money. He wants to exist and engage outside of these walls. It’s a credit to Eden that he ever turns up at all. If you look closer, his left eye is beginning to flicker. He doesn’t appear to have been sleeping much. Eden has weathered the worst of the Lingua Franca experience. His relationship with civilisation is to tolerate things that do him harm. He will only surrender when he can’t get up anymore. For now, he’s still standing.

Lingua Franca

Lingua Franca