- Home

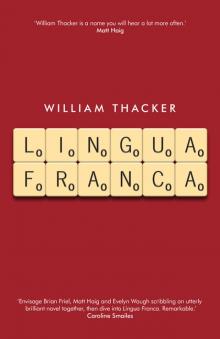

- William Thacker

Lingua Franca

Lingua Franca Read online

WILLIAM THACKER

L I N G U A

F R A N C A

Legend Press Ltd, 175-185 Gray’s Inn Road, London, WC1X 8UE [email protected] | www.legendpress.co.uk

Contents © William Thacker 2016

The right of the above author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available.

Print ISBN 978-1-7850797-4-0

Ebook ISBN 978-1-7850797-5-7

Set in Times. Printed in the United Kingdom by Clays Ltd.

Cover design by The Chase agency | www.thechase.co.uk

All characters, other than those clearly in the public domain, and place names, other than those well-established such as towns and cities, are fictitious and any resemblance is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Author and scriptwriter William Thacker was born in London in 1986. His debut novel, Charm Offensive, was published by Legend Press in 2014. As a screenwriter, William co-wrote the short film, Full Time, winner of the Best Film award at the 2014 Shanghai International Film Festival. He is also the co-writer behind Steven, a feature-length Morrissey biopic currently in development.

Lingua Franca is William’s second novel.

Visit William at

thrilliam.co.uk

or on Twitter

@ThrillWhacker

01. BLUE SKY THINKING

Shortly is an excellent word. It can mean whatever you want it to mean. A member of our team will get back to you shortly. When exactly? Shortly. Imminent is too much. An imminent announcement. Imminent death. Maybe if your death were due shortly, you wouldn’t mind so much. I like shortly. There are three words that should never have made it into English. The first is moist. It sounds bad in any context. The second is phlegm. Just because. And third, worst of all, is flaccid. Flaccid should go. Flaccid should do one.

‘Can anyone hear me? Hello?’

At the same time, there are words which ought to be used more. Like ought. Flummox is cool. Hubbub is great. Genteel. Marigold. Curmudgeon. Lackadaisical? Too much. Rigmarole is a weird one. Have I been put through a rigmarole? I think I have.

‘Hello? It’s Miles Platting! Anyone there?’

I can still remember the important things. I know I made a point of waving my arms – an SOS signal – long in advance of getting hit. I was standing there, a lone man on an island, under a deluge. It seemed to happen in an instant; I opened my eyes and couldn’t tell what was water and what was blood. We had a fortress, a town-within-a-town, and then it happened. The sea punished us for having built with cheap plywood. All around me there’s junk from the unit base: broken teapots and furniture legs, corrugated iron and splintered wood. I’m surrounded by objects that have no place underground: a garden gnome, porcelain rabbits. There’s a kettle with its spout missing, a car boot sale gone wrong. Words come into my head for no reason, words like rigmarole. Most of the time, I don’t really think of anything. I think of Kendal, and then I have to think of something else.

The escape plan is weather-dependent. If the rain loosens up the rocks, I’ll reach up and climb my way out. The extent of my movement is limited to looking left or right. I’m on a live TV pause. To keep myself entertained I’ve taken to counting woodlice. One woodlouse… two woodlice… I should think of a name for the slug crawling next to my shoulder. Bertie, perhaps. Bertie the slug. A slug isn’t a great name for a living creature. It should be something more onomatopoeic: a slimer.

I get a sense that someone’s a few feet above my head, picking their way through the rocks. All I can rely on is the searchlight, which does its best to shine upon tin cans and clothes pegs. Every object except me. I can see its movement on the rocks – it snakes in and out of each gap except the one in which I’m stuck. I find myself cursing whoever’s in charge of the light, and wishing they would give it to someone else.

‘I’m down here! Miles Platting!’

The light no longer shines. I can just about manage a bad-tempered wheeze, the slow pull of an accordion that stretches all my limbs. It adjusts my body so that I’m now facing the slime of a rock, something I’d spent hours getting away from. Above ground, they’ll reconvene at what remains of the unit base. If Nigel’s around, he’ll reproach them for not having better planning procedures. They’ll talk about the logistical difficulties in moving all the rubble. They’ll analyse historical case studies that suggest I’m already dead. They might even place a stone on top of me. They ought to keep searching until I’ve run out of air bubbles, or my stomach’s finished eating itself. I might have become a sensation, a running media story with everyone asking where I’ve gone and whether I’ll be found. I’ll be a hero on the basis of my existence. Or maybe no one will care. What if no one cares? What if there aren’t any cameras? It would be a shame if no one organised a night-time vigil or a ‘pray for Miles’ campaign. There is a process in the event of my death. There is a prepared statement, which expresses shock at the sudden manner of my passing. It urges caution, since the police need time to conduct an investigation. There will be a media strategy designed to maximise the goodwill of the nation. Lingua Franca will be closed the next day; a minute’s silence will be staged. The statement will conclude that murder has no place in a modern society, or indeed an ancient one. Nothing will stop Lingua Franca from exacting its duties. Our determination to carry on is unshakeable. A decision about Miles Platting’s successor will be made in due course.

Something drops in a heap: a coil of rope. The sound of a drill comes next. From my angle, which amounts to a gap in the ceiling, I can see a couple of men in fluorescent jackets with torches on their heads.

‘Hello! I’m down here! I’m Miles Platting!’

I can see one of them put a finger to their lips like I’m going to cause an avalanche. Their method is to remove one rock at a time. One of them snips the tangled metal with a pair of cutters. The other is attached to a bungee harness; he descends until I can almost touch him. I lift my arms like a baby in a high chair, waiting for him to carry me free. ‘Thank you!’

He looks at me and says nothing. What a pro! I cling to him. I say what a nightmare it’s been, how I’ve been stuck here for god-knows-how-long with nothing to do but lick the rainwater and talk to slugs. I cut up my leg and I probably have blood running down my shin. Nothing’s broken, I think. I fell from the front of the boat and I must have landed before everything came down on me; I feel entombed, almost. Apart from that, I’d like to know if the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been resolved, and who won the Ryder Cup. He smiles at my questions but gives no answer. He yanks on his rope and we rise together. I’m leaving behind the underworld. So long, twisted metal. Arrividerci, jagged rocks. I’ll miss you, Bertie. Above me, I can see rescue helmets and thick, grey cloud. Then suddenly I’m out into the half-light. I blink and splutter like someone’s turned on a light and woken me up. I wince, which is the most comfortable thing to do. There are ambulance staff and a crowd of people I’ve never seen – they see that I’m standing upright and they clap their hands. I’m released from the belt and held in place. I don’t have much strength in my legs – the baby is learning to walk. I’m guided down the pebble verge. Someone puts a towel over my shoulders. All around me there’s strewn clothes and litter. I can see broken porcelain which p

robably comes from our kitchen sink. I recognise the portable toilet in its new context: floating in the sea. Dotted along the shoreline I can see red and yellow metal sheets – the fragments of each shipping container. The table tennis table is broken. Most of the sleeping pods have been wrecked completely. A mess is what it is.

‘Where is everyone? Are they alright?’

No one seems to know. Or no one’s going to tell me anything. They take me along the shoreline; they accompany me on my limp. I notice the remains of our kitchen: the fridge and the cooker are gathered in a heap. The sea remains calm. It doesn’t hold itself responsible. On the wooden dock, someone’s put a line of shoes. I can see a red Adidas trainer belonging to Darren, and Nigel’s leather Oxfords. I can’t see anything of Kendal’s. I suppose that’s a good thing.

I catch sight of myself in the ambulance wing mirror. My hair is beyond the out-of-bed look, beyond ironic. My normal instinct would be to shield my face from any cameras. We’re supposed to be indestructible. We’re Lingua Franca. Look on our works, ye Mighty, and despair! I’m not sure that really matters anymore. I’m not sure we even exist.

‘Can someone tell me where everyone is?’

They open the ambulance doors and help me clamber inside. I’m lifted onto the thin, hard mattress, which reminds me of being in a school medical room. I’m glad to hear the ignition.

*

I’m taken somewhere, but I don’t feel conscious enough to know what’s going on. I’m unloaded onto a trolley and suddenly we’re moving at speed. In a small medical room they inspect me, feed me and dress me in a blue patient gown. I can tell by their smiles that I’m welcome, but no one says anything. It’s like I’m a murderer who’s been caught. It seems I’m entitled to free medical care but the silent treatment too.

The doctor has shoulder-length grey hair and reminds me of a grey squirrel. It’s a large permed hair-do, and I wonder for a moment whether concussion can transport you to the 1980s. She retrieves a sheet from the holder on the wall and lays it fresh on the table. She finds a pen and concentrates on her handwriting, as if good handwriting were the most important thing in the world. She lifts the sheet so I can look at the words.

Miles, welcome to Furness General Hospital. We’re going to help you get better.

She puts a dot where she wants a reply. She gestures for me to write what I’m thinking. There’s enough white space to accommodate a full exchange.

‘Where’s Kendal?’

She looks at me like I’ve caused offence; I’ve entered a sacred building and said the worst thing possible (which happens to be anything in the English language). She turns around and starts tending to another patient, who looks determined to sleep, but unable to. I can feel myself frowning as I write on the page.

Where’s Kendal?

The doctor smiles over-animatedly. She seems glad about my participation. She takes back the sheet.

You can see Kendal when you’re better.

She looks at me and expects me to write something. She wants me to play the game. I lean as far as my ache will allow. I draw something.

>:-(

I don’t relinquish the pen. I write in big letters.

Do you know where she is?

The doctor confers with a nurse; I notice the movement of their hands. They seem to rely upon hand gestures and body language. The doctor employs some sort of finger spelling. The nurse nods.

I lean up in bed. ‘Hello?’

Each of them make a shushing sound. They pull the curtain to conceal me from the ward. I’m enclosed. Trapped again. I feel like I want to get up and run. I look at the monitor which displays my heart rate bleeping faster. The doctor slips through the curtain and puts a hand to my forehead. She unscrews a lid and empties some pills into a glass of water. The doctor writes what appears to be a longer sentence or two.

Kendal’s fine. But you’re not allowed any visitors until you’re better.

I’m fine.

You’re ill, Miles.

This time I say it. ‘I’m fine.’

She shakes her head. I’m a bad patient.

‘What is this place? Where is everyone?’

She tells me again – in writing – that I’m ill. She tells me that my memory’s bad and I should write down everything I can remember.

As soon as you’re better, we can help you find Kendal.

She offers me the pen. She looks at me, waiting for something. I have the pen, and apparently that’s all I need. I might as well start from the beginning.

02. THE CAT THING

I first conceived of Lingua Franca at a post-colonialism lecture in Wonga, the county town of Worcestershire. The guest speaker, Kendal, gave a presentation titled ‘Geographical Renaming from Abyssinia to Zaire’. She listed historical examples of renamed settlements, de-Stalinised towns, and asked whether St Petersburg by any other name would smell as sweet. Stalingrad, Stalinabad, Stalinstadt, Stalinogorsk. Peking, Constantinople, Danzig. I listened to everything Kendal said, and I decided that the Czech Republic would be infinitely cooler if it was still called Bohemia. Out of this came Lingua Franca.

‘Good afternoon, sir. My name is Eden and I’m calling from Lingua Franca. Is the person in charge of the council available? Oh, it’s just about naming rights for the town. You see, here at Lingua Franca we specialise in increasing the revenue of town councils by… okay, not to worry, sir.’

I listen for anything which deviates from the script – we’re Lingua Franca, naming rights specialists, and we’re here to partner with your town and reduce your debt burden. Does that sound like something you might be interested in, sir? The lads – and they’re all lads – must always follow the script. To some extent they can develop their own style. Some of them wear headsets, which allows them to use both hands on the keyboard. The majority like to stand when the call is happening. They know when I’m listening; the tone of their voice hardens. They’re not going to let me down.

The emergency alarm takes the form of an intermittent beep. It stops the whole office from performing their duties – you can’t make a sales call when there’s a loud beeping noise all around you. When it sounds, most of the guys look up from their small, note-ridden desks as if to say What do we do? Is this a reprieve? Do we get to smoke and pretend we do something else for a living? They look at me, and they look at Nigel; after all, we founded this company, and we tell them what to do. Nigel claps his hands and tells them to evacuate via the stairs.

What impresses me about Nigel is how calmly he locks the panic room. We sometimes share it with a finance company, but only if they get here fast. Otherwise we shut the door. We like to entomb ourselves. There is a small window, which gives the faint impression of freedom. The glass is strong enough to withstand a hail of rocks. In fairness, it can only be breached if someone is determined to kill you. They’d have to fly a remote-controlled helicopter and somehow shoot bullets from its undercarriage.

Nigel talks on the phone to security; he nods, which means something’s happening. He puts down the receiver. ‘Guy with a knife.’

The routine is so familiar that it no longer makes me nervous. It’s boring, more than anything. The lads are standing in the car park. They like alarm drills because it gives them a chance to smoke. They don’t realise that I’m watching them – they push each other around and wrestle. It makes me worry that they behave in such a toe-the-line way when they know I’m watching, but like animals when they think I’m not. I serve a function in their lives: I authorise their pay cheques, write their references and manage their self-esteem. My power is conditional. From the window you can see how the modern part of Stella Artois has been planned. The roads form a rectangular grid – a Belgian waffle in town form. There is something calculated about it. There is a section of raised motorway and a polluted canal. If your eye is drawn to anything, the shopping centre is the obvious thing. The roads seem to converge towards the shopping centre, making it the cathedral. It has grown ugly, the town. On

the horizon is a small neighbourhood called Stella Artois Old Town. Here, the street pattern is less sensible. There is a hint of picture book England: a church, some timbered pubs and a bowling green. The residents have a fondness for conservationist groups, duck ponds and anti-miscegenation laws. I dislike Stella Artois Old Town.

Everyone begins to regenerate, slowly coming back into the world as the person they once were. I only have to look at Nigel for something to happen – he’s my yo-yo, and I unfurl him when I want. He does the clapping. He shouts, ‘Gather round, guys.’ Everyone in the company assembles in a circle. We begin the expression session. Nigel points to the head of operations. ‘Ops! How’s your week going?’

She says ‘Good, thank you,’ with no added joke or banter, no tacit acknowledgement that in our preferred world none of us would be standing here talking about the daily processes of a naming rights agency. ‘We had constructive dialogue with Carlisle, who want to rename one of their car parks. We’ve got a couple of automotive brands interested in that one.’

‘Tell them we’ll get back to them shortly.’

Everyone nods. No one wants to look uninterested. ‘And our highlight for the week was the Friday night social, which was super-fun.’

Nigel smiles and thanks the operations manager. Then he turns to the head of sales. ‘Sales – what are we forecasting for November?’ Nigel has his pen primed, ready to make a note.

‘We estimate thirteen.’

‘Including Stevenage?’

‘Including Stevenage.’

‘What happened to Motherwell?’

‘Motherwell’s gone cold.’

‘Pity, because Mothercare would have been a good match.’

‘It would have made sense.’

‘Thank you, sales. Who am I missing? Localisation.’

The head of localisation talks about the rebranding of Skegness, which was six months ago. It’s now called Vue, after the cinema company. ‘We’re in the process of renaming Skegness Pier, which is going to be called Vue Pier, but possibly with Vue spelt view, subject to focus group polling.’

Lingua Franca

Lingua Franca