- Home

- William Thacker

Lingua Franca Page 4

Lingua Franca Read online

Page 4

We walk a little further, under the motorway, and emerge outside the office.

‘Do you need to go anywhere else, sir?’

‘No, I’m fine from here.’

‘You never know who’s out there, you know.’

‘Thanks.’

There is an order in which Darren’s supposed to ask me things. One of the questions is meant to be ‘Have you had a good afternoon?’ which will probably come soon. He squints as if he’s trying to remember something. ‘Have you had a good afternoon?’

‘Yes, Darren.’

He walks me as far as the fob entrance. With no advance warning, Kendal walks towards us with four bags of shopping. She has no freedom of her hands; she’s weighed down like an unbalanced pendulum scale. She’s unable to prevent the wind blowing her hair back. There is no longer a duty to keep opinions to oneself. She puts on a respectable third-party smile on account of Darren’s presence. She looks happy I have company, which means I’m not in imminent danger of being killed.

‘Another day of ruining the world?’ She looks at the office tower as if it were something to pity.

‘Something like that.’

She nods. She wants me to know she can talk about work, but only if she’s allowed to emphasise her disgust. ‘We’re doing a roast next weekend. You’re invited.’

‘But they hate me.’

She rents a couple of bedrooms to her teacher friends. It’s easy to imagine them sitting in the kitchen at night, discussing how awful I am. I’m not a monster exactly, but our separation has given Kendal’s friends the freedom to say whatever they like.

‘It’s a triple date. I need a partner.’

‘Why can’t you find one?’

‘Because there aren’t any fucking men in this town. They’re all IT contractors. Bank managers…’

Darren spends a moment looking at his shoes. We make no effort to integrate him. Darren’s the rope and we’re the tug o’ warriors.

‘You should meet Eden. He’s depressed.’

‘Who’s Eden?’

‘He works here. I stalked him the other day.’

‘Why?’

‘I wanted to see what his life’s like.’

‘What’s it like?’

‘Shit.’

She mentions how she once taught an Eden as a teenager. She sees him around sometimes. Cropped hair, grey beard.

‘That’s the one.’

‘He was a poet. Or at least he wanted to be.’

‘Well, he works in telesales now.’

She likes to stay in touch with her pupils. They’re no longer pupils but she still thinks of them as such. ‘Give him my love.’ It’s a shame that Kendal should have any connection to our workplace. She doesn’t need to know what we’re up to. All she’s meant to know is that we’re making money and we’re able to live as a consequence. That’s what we do. It’s to Darren’s credit that he’s able to stand and listen. He exists on the margins, always there but never belonging. Kendal lifts her shopping and smiles at Darren. ‘Keep him safe, will you?’

‘Yes… lady.’

He avoids eye contact, doing the routine of a Buckingham Palace guard. He probably wanted to say Mrs Platting. He lacked the conviction. Kendal says she will call me about the roast. She waves as if I were standing far away. There’s no kiss on the cheek, which is a shame, and something to reflect upon.

*

It’s not a day in which anyone can do much work. It’s a day in which bodies are allowed to recover and minds allowed to rest. Everyone seems to be in a general state of disrepair. Some of them have trouble clearing their throat. No one seems to have washed. It’s not just the effects of alcohol – it’s the unrequited love, unanswered text messages, cheating on partners and all the things that account for the spike in internal email traffic. I hang my coat on the hook. There’s a general understanding that I’m the only one who’s allowed to be late. Straight away there’s a queue of young graduates, who smile for my attention like I’m a waiter who hasn’t brought the bill. I look at my mobile as I walk – an excuse to avoid their gaze. I get halfway across the room.

‘Miles, can I ask you about the logo?’ The graduates tend to ask lots of questions. They prefer problems to solutions.

The next one says, ‘When you’ve spoken to Karen, have you a got a moment to look over the press release?’

Someone else says, ‘When you’ve spoken to Ed, can you check the voiceover?’

I raise a hand and signal no more questions. My method of leading by example is to avoid leading anything. ‘I’m happy for you guys to deal with it.’

They all seem to shrink at once. If they say anything, it’s a simple ‘of course’. It takes a while for things to regain their usual rhythm. The tech team monitor social media for any attempts to kill us. The digital marketers analyse online traffic as a means of gauging excitement. The graphic designers sit in a circle and discuss the brand values of Barrow-in-Furness. Most of the noise comes from the telesales desk. They’re talking to Cleethorpes, Bognor Regis and Westgate-on-Sea. Their objective is to overcome resistance.

‘Forgive me, sir, but are you honestly saying you want to leave two hundred grand on the table just for the sake of tradition?’ Eden lets out a laugh. ‘I mean, fine – if that’s financially viable. But what would your constituents say?’ There’s much to admire in Eden’s work. He combines the graduate outlook with real-world schtick. His patter is better than anyone else’s. ‘Okay, sir… yes, no problem, sir. I’ve been called a lot worse, sir…’ He always puts down the phone in the loudest way possible. ‘That was a train wreck.’

‘It sounded good, mate. Who was it?’

‘Lincoln.’

‘Lincoln? That’s not a shithole. Don’t be so hard on yourself.’

We’re in a race to sign-up a honeypot town, somewhere with a castle or cathedral. There are 48,083 UK cities, towns and villages. On the wall is a table with thousands of UK settlements ranked according to average income, number of graduates, job prospects, house prices and such. We index the towns using a colour code: the golden towns are the likes of Cambridge, Bath and Oxford, none of which will take our calls. Then we have the yellow tier, the minor posh towns that lack brand value, the Winchesters and Cheltenhams. Then it’s the beige: Reading, Colchester, Maidstone, Northampton. Finally, the bottom of the table is where most of our activity is focused – towns with low-employment and low visitor numbers: Cumbernauld, Canvey Island, Barrow-in-Furness. The brands, of course, are limitless. Our partnerships team engage with businesses, take them to lunch and persuade them of the benefits of town branding. We have 150 companies waiting to bid for each town’s naming rights. The towns sign up on the proviso we can pair them with a suitable (and lucrative) naming rights partner. Following a sale, our partnerships team advise the town on which naming rights partner would resonate with their constituents. We might suggest that affluent Edinburgh be renamed after a chic wool company, or that progressive Bristol call itself Planet Organic. When the bidding commences, the naming rights for somewhere like Ipswich might fetch a couple of million a year, but an Oxford or a Cambridge would attract hundreds of millions. I present myself to the room as open-to-business. ‘Listen up, guys. I want to see more historic towns. More spires, yeah? Eden’s done a great job hammering Lincoln. If you sign up a top-twenty town, I’ll buy you a holiday to Las Vegas. Then you can sign up Las Vegas.’

In tandem they consult their computer databases, lift their receivers and whisper with one another about who’s got Windsor and who’s got York. Eden photocopies something – a completed direct debit form – which he likes to keep in a drawer. He’s organised, even when it comes to things that don’t affect his ability to make a sale. Eden puts the form on his desk. He stares at me and says he’s going for a smoke. He slings a coat over his shoulder and leaves.

Without Eden, they often lose focus. I look at the team and clap my hands. ‘Give it twenty minutes and you can all have a fag break.�

� I feel comfortable leaving the room in the knowledge that we have something resembling a business. I enter the side office where Nigel is on the telephone.

‘Yes… we’ve got toilet roll. We just need six outdoor toilets. How long will it take to instal?’

There’s a sheet on his desk that lists things like detergent and beer. On the computer screen is a map of Barrow-in-Furness. Nigel’s remit is to arrange the construction of our unit base, the scheduling of events, and to ensure we pay no tax on anything whatsoever. Nigel puts down the phone at last. He hasn’t touched his sausage sandwich. He leans back and sighs, giving the impression he hates his job, when really he’d have nothing better to do. He runs through the list. ‘We’ve got the portable toilets, one table tennis table, one mini-fridge, one big-fridge…’

‘What’s the weather like?’

‘Cold. I’ve ordered some outdoor heaters.’ Nigel leans back and makes a noise of mock exasperation. ‘So much to do!’

‘What about security?’

‘We should put a bounty on the head of your eventual killer. What do we think – two million?’

‘Just get a couple of guards.’

‘You can bring Darren.’

‘Fine.’

Nigel has small eyes and a patchy undergrowth beard. He looks like someone who spent his entire university life in a darkened room playing World of Warcraft. He looks over his notes and tries to recollect something about train platforms. ‘By the way, they want to ambush you.’

‘Bring some batons, then.’ History tells us that planning is essential. We’ve learnt from our mistakes. At the naming ceremony, we no longer serve scotch eggs – they’re good missiles. We’ve learnt how to pronounce Clitheroe.

We notice some of the graduates pawing at the window, somewhat distressed, as if they were trapped in a sinking ship. The door swings open and we’re told to come and look. Everyone now seems to be gathered at the window, staring at something. It seems that all the activity has stopped. The telephone is ringing and no one seems to notice. The focus is on the roof opposite, where someone is crouched at the edge like a cautious swimmer thinking about whether to plunge. I’ve bitten my lower lip but I don’t feel the sensation. Is it really Eden? Is it just an Eden lookalike who’s going to fix the air chiller? It doesn’t seem likely. Engineers don’t wear chequered shirts. We don’t need binoculars to see that it’s Eden. He looks like he belongs on the roof. He doesn’t care that we’re just opposite, with our hands pressed against the glass. He looks focused. He doesn’t seem to notice our waving hands; we’re a football terrace trying to distract the penalty taker. To Eden, we must look like the ones who need help.

‘Nigel?’

Nigel doesn’t have a protocol. There’s no precedent, which means he’s got nothing to refer to in the brand catalogue. He walks in between the onlookers, making a quiet, strange suggestion that everyone should disperse. He says, ‘Nothing to see, ladies and gents,’ but he doesn’t get a response. There’s plenty to see. No one from street level seems to know what’s happening. There are people entering and exiting the train station. The pigeons watch from the roof opposite.

I want to believe Eden’s looking at me, even when he’s looking straight ahead. Only he can understand what’s happening. He seems relaxed. He just wanted to go outside for a smoke. He happened to find the emergency stairwell. That’s all that’s happened. He rises to his feet. He appears to size up the space in front of him. He breathes out and causes us to brace.

‘Eden…’

He looks at us – all of us. He closes his eyes. Some of the women begin to scream. The lads wave their arms and shout. He darts into a sprint and leaps mid-air into the only thing he’s sure about, the only thing that’s certain.

05. BRAND REPOSITIONING

They’ve not given me enough paper. On the floor are the strewn sheets with everything I’ve written. The doctor passes one of the sheets to the nurse, who passes it to the psychiatrist. Everyone’s reading my story. I focus my pen on the only remaining white space.

Get me some paper.

The nurse breaks out into dimples. The grey squirrel nods. They’re happy that I’m playing the game.

In the absence of something to write on, I can only use my voice. ‘Vamos!’ They seem to be panicked by this. The nurse rushes to the drawer and looks inside. She returns with some clean paper. I rouse myself into a sitting position. The nurse puts a pillow behind my back. She pulls down the retractable TV screen and makes sure I know how to turn it on, and where I can access the silent films. She grabs a pen from the desk and writes:

You’re doing very well.

She does everything with a smile. She endorses every aspect of my being, so long as I say nothing. The cleaner takes my cup. The physiotherapist rubs the sole of my foot. All I need is a gold star. I seem to command most of the attention. The bell rings from another bed and the nurse ignores it. The bay has six different beds, all occupied by males. I’m reminded of the times I’ve been brought together with strangers, like my freshers week a long time ago at Southampton University – now The Wagamama Institute. The patients seem to be half asleep. One of them has a foot suspended in a cast. Every now and then someone makes a groan. It’s hard to tell whether they’re deteriorating or just can’t be bothered anymore. It’s as though I’m the only one who’s alive.

A trolley comes and the caterer puts down a tray – mashed potato and a metal cylinder of vegetables. She presents a menu with different dessert options. I point at the BlackBerry tart, formerly Bakewell tart. I write a note:

Mustard, please.

The caterer turns to her colleague and makes the letter ‘M’ with her middle three fingers. The message is understood. I peel the cellophane wrapper from my plastic tub of gravy. On the TV screen is a weather report. I put on my headphones and realise it makes no difference because everything’s been muted. The weatherman is talking aloud but the words are subtitled. He points to South West England, to Allianz, where temperatures will drop to within nine degrees celsius. In Pfizer, Surrey, there’s every chance of rain. The Environment Agency has issued a warning about driving conditions in Cath Kidston. The nurse adjusts the room temperature. I raise a thumb. In the corner of my eye, the grey squirrel accompanies a patient into the corridor. I remove the headphones and put the tray on the side. I swivel into a sitting position and pull the slippers onto my feet. The nurse seems to watch.

Where are you going?

I make my first attempt at sign language by pointing to my crotch. She corrects me: you’re supposed to do a double-tap of the shoulder blade with your index finger. Next time I’ll know.

If you’re looking for Kendal, you won’t find her.

Why?

It’s a big hospital.

Where is she?

The nurse makes an exaggerated shrug. She passes my note to the physiotherapist, who does the same thing. It would make sense to indulge the game and see where it gets me.

I was hoping she’d be here.

You can see her when you’ve recovered.

But I’m fine.

The nurse leans down to remove a can of Heineken from the trolley. She puts it on my bedside table. I’ve never met a nurse who encourages bedside drinking.

Aren’t you going to tell me what happened next?

She looks at me with the expectation that whatever I write is going to be amazing. She wants to know the rest of the story. I’m made to feel like I’m cute. I’m interesting. I tell great stories with my pen and it’s not what I write that’s brilliant so much as the way that I tell it. I should just write as much as I can, and speak aloud when I can’t find the words. I’ll write about Kendal, and Nigel, and all the others. All I need is a can of Heineken – the beer, not the place in West Yorkshire.

*

In the moments after Eden falls, Nigel gives a creditable performance. He writes an email to all members of staff, emphasising the need to remain cautious. For some reason, he states that Eden w

ould never do something so stupid as to take his own life. It must have been an accident. When it comes to phoning the police, and recording what we’d seen in writing, Nigel makes a point of working until the necessary duties have been done. This is Nigel’s preferred state of affairs. He likes everything to be a procedure. He wouldn’t mind if every day was a crisis.

Nigel finds me in the side office. ‘He left this on his desk. I’ve made a photocopy. I’ll give the original to the police.’ Nigel puts it in front of me. It’s a completed direct debit form signed by Eden. On the other side is a handwritten note. ‘I don’t think you want to read it, mate. It’s not all bad. But he’s not our biggest fan, put it that way.’

I stare at the letter without taking in the words. I fold the letter and put it inside my jacket. ‘Another time.’

Through the glass we can see the office as we’ve never seen it before: idle and silent. They seem to be facing one another, consumed for once in each other’s company. The sales targets on the board might as well belong to another age. Nothing seems important except to love and support one another. In our own little cell, we mimic their silence. We sit and say nothing. Nigel lacks the humanity to construct sentences that feel appropriate for the moment. ‘Puts a spanner in the works for Barrow, doesn’t it?’ I look at Nigel as though he were deserving of pity. He seems to take note of this. ‘I’m just saying.’ We look at the room opposite. There’s nothing in the rulebook, no guide to consult. ‘They’ll expect you to say something, mate.’

‘I know.’

Nigel never says ‘mate’. In a normal situation, it would sound wrong coming from Nigel. In the context of Eden’s passing, it feels warm and sincere. It was the right thing to say. I let Nigel put an arm around my shoulder. Then we step aside and make sure we don’t make eye contact.

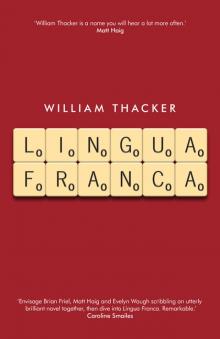

Lingua Franca

Lingua Franca