- Home

- William Thacker

Lingua Franca Page 7

Lingua Franca Read online

Page 7

She pulls up a chair and sits on the table, closer to the students. She wafts a hand in my direction. ‘The floor is yours.’

I take the opportunity to pace around the room. I begin my own cross-examination. ‘I also agree that language matters, but so does progress.’ This is a good way to start. ‘Progress isn’t just about freedom of expression. There are hundreds of towns across this country where people can say whatever they like, but what voice do they really have?’ Almost by accident, I seem to have said something worth listening to. They’re silent for once. ‘And there’s a moral point here.’ I raise a moral finger. ‘Do you want local services? Care in the community? Do you want your rubbish picked up from your street? Libraries. Health visitors. Childcare. These are the things that matter. And sadly, they’re not free.’ I’m encouraged by the silence. There’s an opening. I’m through on goal, with only the keeper to beat. ‘Do you want to live in a town that’s miserable, dirty and bankrupt, just so you can cling to some old romantic notion? Or do you want to live in a town that’s prosperous, vibrant, fun. Wi-Fi enabled! As I said earlier, we own language. It doesn’t own us. And naming rights is nothing new. We’re not doing anything the Romans weren’t doing when they called it Londinium.’

They seem…numb. No one knows what to say. And not because they disagree. Just because some things are too awful to agree with.

‘Rubbish,’ Kendal says.

‘Is it?’

‘Yes!’

Some of the class also shout ‘yes’. This is their escape. A reason to believe there’s more to life than what cynical Miles Platting says. Kendal offers them a dream. If you could sell that, it would be bigger than Burger King.

‘Why should we rename our towns after biscuits or washing powder?’

‘If I paid you enough money, would you change your name?’

‘No.’

‘So, let’s say I offer you a million quid to call yourself the name of a biscuit. Would you do it?’

‘I’ve already got a name.’

‘But now I’m calling you Wagon Wheel, and everyone has to call you that. But you get a million quid. Are you seriously telling me you’d turn it down?’

‘You can call me HobNob. And we’ll call you knob.’

That’s the key line. The uppercut. There’s damage, and I can feel it. They laugh hard. They laugh because they have to. I smile to mitigate the damage, which shows I’m on their side. I’m not against laughter. I try to regain control. ‘As long as we can communicate, and write as we please, what’s wrong with naming a town after a biscuit company?’

‘It’s about a corruption of language. We’ve turned our language into a commodity.’

‘How do you expect councils to pay their bills?’

‘Just like the rest of us.’

‘We’re not selling poison. Take a walk round Jacob’s Creek. Visit Hyundai. Look at the difference we’ve made.’

‘Do the people of Hyundai want to grow up in a car?’

‘It’s better than living in a ghost town.’

‘It’s a false choice.’

‘No, it’s not. You’re punishing them. You want to pull the rug from under their feet.’

‘You want to name the rug Sports Direct.’ She seems happy with this line. She’s winning most of the laughs. She speaks in riffs – little one-liners that stay in your mind. More than anything, it’s become a comedy contest. Kendal is smiling. She has earned the right to smile. ‘You think there’s nothing sacred,’ she says. ‘You think everything can be bottled and boxed and turned into a product. You have no respect for the human experience. You turn everything cold. All you do is convert people’s hopes and dreams into profit. You know the price of everything and the value of nothing!’

The applause is such that I can only raise my voice. ‘That’s not true.’ They’re addicted to applause. They would clap almost anything so long as it had a rising, rhetorical flourish. They’re young, clapping seals. If anything, the goodwill surrounding Kendal intensifies. She does nothing to squander it. She could say nothing and it would still be enough. They’ve made up their minds. They choose virtue over vice. Someone else can make the hard decisions. What’s important is that they feel good about themselves. It feels like the end. There should be a klaxon. Some of the students stand and applaud. If they were watching a boxing match, they’d call for the bell. It’s difficult to change the mood. Kendal looks at me and shrugs as if to say shall we wrap it up? There must be an end to everything. She offers a hand; we shake. She addresses the room and asks what they thought.

‘Raise your hand if you agree with me.’ There’s a near unanimous show of hands – they were racing to see who could raise their hand first. ‘And who agreed with Miles?’

I look at the audience. How many hands do I have? One… two… three… I don’t have many hands.

08. STICKY TOFFEE PUDDING

I open the gate and notice the problem tree, with its growing colony of fungi. I think about whether I should make a joke about being a ‘fun guy’. I decide not to. The wheelbarrow’s gone, replaced with an empty shopping trolley. Trust Kendal to go on a last-minute trolley-dash for fig rolls and crackers. She said to bring nothing – the first round of mind games. She told me not to cook, and certainly not to bring flowers. If I want to be helpful, I can learn a little about the other guests – the worst task of all. Most of all, my involvement extends to coming along and making all the jokes. In the absence of music, or a sign at the door, I worry for a moment that I’ve got the wrong day. There’s a light from the corridor. I raise a hand and knock three times. Kendal’s coming down the stairs and checks herself in the mirror. I know it’s going to be a long night the moment Kendal opens the front door. She’s wearing a party hat and says my name in an over-animated, insincere way. It means that everyone is here and they’re listening. I enter the hallway and it’s only when the guests come into view that I pull the pink roses from my bag. Kendal’s forced to smile in recognition that I’ve done a generous thing. It’s a shame for Kendal; she’s lost the first round of mind games. I smile and she knows why. I seem to get everyone’s attention. Having met Kendal’s teacher friends before, I don’t believe they’re terribly burdened by interaction with the male species (and probably all the better for it). One of the women rises from the bean cushion and leans to kiss me on the cheek; she manages not to spill the wine glass in her hand.

‘How do you pronounce tortoise?’ she says.

‘Pardon?’

‘Wait, wait, wait. I can’t give you a clue. How do you pronounce… you know, that shelled creature – like a terrapin.’ She makes a hand gesture to indicate going-for-a-swim. She still hasn’t said hello.

‘Tortoise.’

‘Yes!’ someone says.

‘No one can pronounce it.’

They do a ‘sorry, sorry’ routine and proceed to introduce themselves again. They’re teachers, but they’re allowed to have fun tonight – they want to stress this point. Almost straight away I’ve forgotten their names. Kendal passes me a glass of sparkling wine. There’s a double-knock at the door and a man enters. He has a dark, receding hairline and his arrival prompts a similar sort of cheer to my own, only higher-pitched and perhaps more dishonest. Kendal points me in the direction of the new arrival, which leads to a handshake and a ‘hello, mate’ kind of thing.

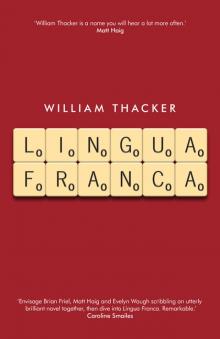

‘Miles runs a company called Lingua Franca, a naming rights agency.’

‘Oh right.’

I’m immediately invited to justify myself. I proceed to explain the purpose behind Lingua Franca, and our intention to rename every town in Britain after a corporate sponsor. I mention that we’re visiting Barrow-in-Furness tomorrow to mark its renaming as Birdseye-in-Furness.

‘I’m going to visit you,’ Kendal says, which has never been mentioned before. ‘I want to see how it works.’ The mind games continue.

From the other side of the room there’s a sudden clamour of ‘Yeah, how does it work?’ I’m required to e

xplain the process – the ribbon-cutting, changing of signs, map reconfiguration – and while they listen to what I’m saying they don’t do a very good job of taking it all in. Their response is to say ‘right’ in order to show they’re listening without endorsing anything I say. They wait for pieces of information they find problematic before deciding when exactly it’s appropriate to wince.

The new arrival’s brain catches up with the rest of the room – which isn’t far to travel. ‘Oh, I have heard about this.’ He will have read about us in the free newspapers on trains. Some of the broadsheets have also featured us – often in negative column pieces – but the main reason for the media interest is the fact we’re a gimmick. You often find features imagining what kind of outlandish brands could replace the names of classic British towns. When we first started, the public regarded us with a certain curiosity. We were presenting a new idea – or at least an extension of an old idea – and people seem to like newness, no matter what it entails.

‘Miles is angry with me because I undermined him in front of my class.’ Kendal exits the living room; she just wanted to plant a seed.

‘How did she undermine you?’ one of the women says.

‘Just the usual stuff. My company, my commitment to evil…’

They laugh, because they’re supposed to. I need a distraction. Something smells like chicken stock. I mention what a great job Kendal’s done with the hosting. Kendal shouts for someone to switch on the music. She calls for something else but no one knows what she’s saying – it becomes a temporary source of amusement in the absence of anything else to laugh about. There’s another knock on the door, another male. The triple date is underway. It starts again, the excitement and the handshakes. I end up repeating my story about how Lingua Franca came to dominate our lives. Kendal enters with a hot tray containing the stuffed chicken and roast onions. She’s wearing oven gloves but she handles the tray like she’ll be scolded any minute. Everyone makes a big thing of applauding the chicken’s arrival. We assemble around the table, ready to accept that we might not get along very well. Things settle down; the food occupies their attention. They’re not focusing on the whys and wherefores of naming rights anymore; they’re focusing on roast potatoes. Kendal makes an effort to integrate the chap with the receding hairline. ‘Remind me what it is you do,’ she says. He takes the opportunity to mention that he works for a consumer rights watchdog. He tells everyone which electricity plan to purchase and the merits of each package. It sounds like valuable work, but not something to talk about for five minutes. Kendal feigns interest by mentioning something about the cost of heating a home – a delaying tactic, which inches us closer to the Promised Land (the night coming to an end). Midway through the first course, the rest of the table acquire a confidence they didn’t possess before. It’s the alcohol that’s responsible. The volume increases – it’s like someone has pointed a remote control at the room and turned everything up. It builds into cross-table chat with everyone’s input but little in the way of engagement.

‘I’m definitely having babies.’ Kendal pours champagne into a flute. ‘The more I think about it the more I like the name Henry. It has a patrician quality.’

Someone nudges me on the shoulder. ‘There you go, Miles.’ I stick my fork into a Brussels sprout. It gives me strength.

‘Miles would make a great father,’ Kendal says.

‘No. That’s not true.’

‘Sometimes you forget how kind you are.’ I want to look at my hands. I want to see whether there’s any truth in what she said. For some reason, I think I can find the answer by looking at my hands. ‘We could have a daughter,’ Kendal says. ‘You could pay for everything. The jewellery… the shoes…’

‘She sounds lovely.’

‘The only trouble is that we’d have to have sex.’

It moves onto a conversation about mortgages, the cost of living and something else. Everyone wants to say something. They suddenly have opinions about all sorts of subjects. They’re talking almost as loud as they can and the effect is to neutralise anyone who wants to talk at a normal volume. It gets so loud that I’m the only one who can hear Kendal say there’s more gravy if anyone wants it. It gets to the point where most of them seem to forget what they’re talking about – they just want to shout. It seems to be a political debate, but I’m unable to focus on what anyone’s saying. A lot of the sentences begin with ‘yeah, but how come…’ How come they won’t speak English? How come they’re allowed to wear a burqa? They seem to know the answer to their own questions, as though every solution were obvious; they believe in absolutes, not nuance. Kendal seems on a state of alert. She tries to change the subject to the dessert that’s on its way. Then it transpires that one of the teachers has taken great offence to something. ‘What do you mean?’ she says to the man opposite.

‘Well, you know… it was a joke.’

‘Do you think it’s funny?’

I rise from my seat and start to gather the plates. Kendal looks alarmed. ‘I’ll do it, Miles.’

‘It’s alright.’

‘No really, I’ll do it.’ She tries to wrench the plate from my hands. I manage to resist. I carry the plates to the kitchen. Another victory. I scrape the bones into the bin. I pull the dishwasher door open. I run the tap and start to rinse the dirty plates. I listen to their argument, which is starting to brew. It’s the perfect place to listen. I’m uninvolved, like a cat sitting from a height.

The accuser raises her voice. ‘Don’t try and wriggle out of it.’

‘Come on. Lighten up.’

No one’s in the mood to lighten up. It sounds like he’s being racist again. The two couples align on opposite sides of the debate. The triple date has become a war.

‘When you use that word, do you think about what you’re saying?’

‘Oh come on. It’s just a word.’

‘It’s not just a word though, is it?’

The accused is stern and unrepentant. ‘It was a joke.’

I run the hot tap against a knife. I’m distracted by text messages on my phone; Nigel informs me that we’re leaving at nine a.m and the Barrow officials are looking forward to greeting us. Are you enjoying the turnips? is the next message.

No turnips I reply.

Everyone’s quiet by the time I’ve stacked the dishwasher and re-entered the living room. You can tell that no one’s enjoying the experience of sitting at the table. The only good thing you can say is that all the noise has stopped. My strategy is clear – don’t say anything, and let the others say what needs to be said. I’m on a losing game tonight, but this one’s a winner. I can’t lose from here. I’m taking the ball to the corner flag. I’m running down the clock. I might be able to get out of here. There’s an actual chance I could leave the house as the second or third least popular person. I’ve gained a couple of percentage points. The accused explains that he didn’t mean to cause offence, it was more the fact he wasn’t thinking. ‘I didn’t mean all Muslims,’ he says. It’s agreed that the subject should be dropped. I can feel myself getting ready to sleep, which is contrary to the requirements of the moment.

The next part of the evening is dominated by forced laughter, owing to a game involving strips of paper and a hat. Kendal is laughing but she’s not enjoying herself – I know this because I know Kendal. She’s laughing, but she’s acting. It reminds me that we’re not so different. I notice that one of the guests looks at his watch. The racist says he better ring a taxi. I wonder whether to make a joke about getting a black cab, but think better of it. We spend the final part of the night listening to the consumer lobbyist talk about mortgages. I wonder for a moment if the subject lends itself to racism. This is also what Kendal’s thinking. She looks at her watch. She says it was lovely that everyone made the effort, and we should do it again sometime. She looks like she wants to dip her face into what remains of the mashed potato.

*

‘Everyone in Barrow knows we’re on the nine forty-one,

’ Nigel says. ‘They want to ambush us. The safest bet is to put you in Darren’s van.’

‘Fine.’

‘That way you can avoid the egg throwers.’ There are piles of notes on the desk. Nigel has been drafting the speech for the naming ceremony. ‘The company line is that we’re here to listen. Yes, we understand the negative publicity surrounding Lingua Franca of late, but that’s a thing of the past. We want to revitalise Barrow. We want to make it special. We don’t want Miles Platting to be remembered as the worst man in England.’

‘You’ve beaten me to it.’

At this stage of a project, the side office becomes the nerve centre. The boxes have been labelled as though we’re moving house. Nigel’s written words like kitchen, tech and fun with a black marker pen. On the table, there’s a diagram, which displays each component of the operation: press, web, admin, security, catering and travel. There’s a map of Barrow-in-Furness. Barrow is roughly where I thought it would be – somewhere in the far north-west. I wouldn’t want the people of Barrow to know that I need to look at the map. If you’re going to obliterate a town, you ought to know where it is.

‘I didn’t realise how close it is to the Lake District.’

Nigel isn’t listening. He doesn’t really care about Barrow itself, compared with the process of getting it sold. Nigel is what they call a company man. He will be here long after the radiators.

Through the glass partition, the office maintains its slow, post-Eden rhythm. Everyone’s happy to work, but not quite as motivated, perhaps. Some of them are putting on their coats in anticipation of the departure. The sales team remains focused; they’re the reservists, who will undoubtedly fuck around as soon as we’ve gone. Outside, a team of workers instal a mesh of netting running the length of the window. It gives the impression that if anyone wants to kill themselves, they ought to think again. Nigel pulls out a sheet of paper.

‘That’s the speech. Learn it.’ He rummages through the contents of his drawer; he asks whether I’ve seen the train ticket receipts. Then he mutters something about linen. These are the moments where Nigel needs to be alone. I step away so he can get on with the business of losing his mind. I’ll meet him in Birdseye-in-Furness.

Lingua Franca

Lingua Franca